Here is the next chapter of Lessons not Learnt: The 2015, 2017 & 2019 General Elections direct to your inbox.

In this chapter, we explore how in each general election in the UK, in so many seats the result is a foregone conclusion.

Chapter 7: Safe Seats

Another recurring feature of FPTP that was in evidence at all three of the last general elections was the large number of safe seats, where parties are almost certain to win. The certainty of safe seats can breed complacency among parties and lead to voters being taken for granted, with safe seats ignored during election campaigns while seats that may change hands are lavished with attention.

Before the 2019 election, the average UK constituency had not changed hands for 42 years, with 192 seats (30% of the total) last changing party in 1945 or earlier, and 65 seats (10% of the total) being held by the same party for over a century. These ‘one-party’ constituencies mean that other parties can build up substantial vote shares in particular areas, yet never achieve the representation they merit.

In 2019 and 2015 we were able to predict the outcome in half of all seats in Great Britain before a single vote had been cast. That the outcome in so many of Westminster’s seats could be confidently known before a single voter had gone to the polls is a sad reflection of how many votes are devalued by the system.

Only 79 seats changed party hands in 2019, a small increase on the 70 seats that changed at the 2017 general election, but still representing just 12% of seats across the UK. The 2015 general election saw 111 seats switch party and the 2010 general election saw 117 seats change.

Changes in votes are not being represented by changes in the House of Commons, with many voters locked out of having a meaningful influence on our politics. Voters in safe or marginal seats experience a very different election to each other.

Our polling in the run up to the 2019 election revealed that those living in seats classed as marginal received far more election literature than those seats classed as safe for one party or another.

Just one in four people (25%) in safe seats reported receiving four or more election leaflets or other pieces of communication through their door compared to almost half (46%) of those in potential swing seats. Nearly three times as many people in swing seats (14%) reported receiving 10 or more leaflets or other pieces of communication, compared to just five percent of those in safe seats.

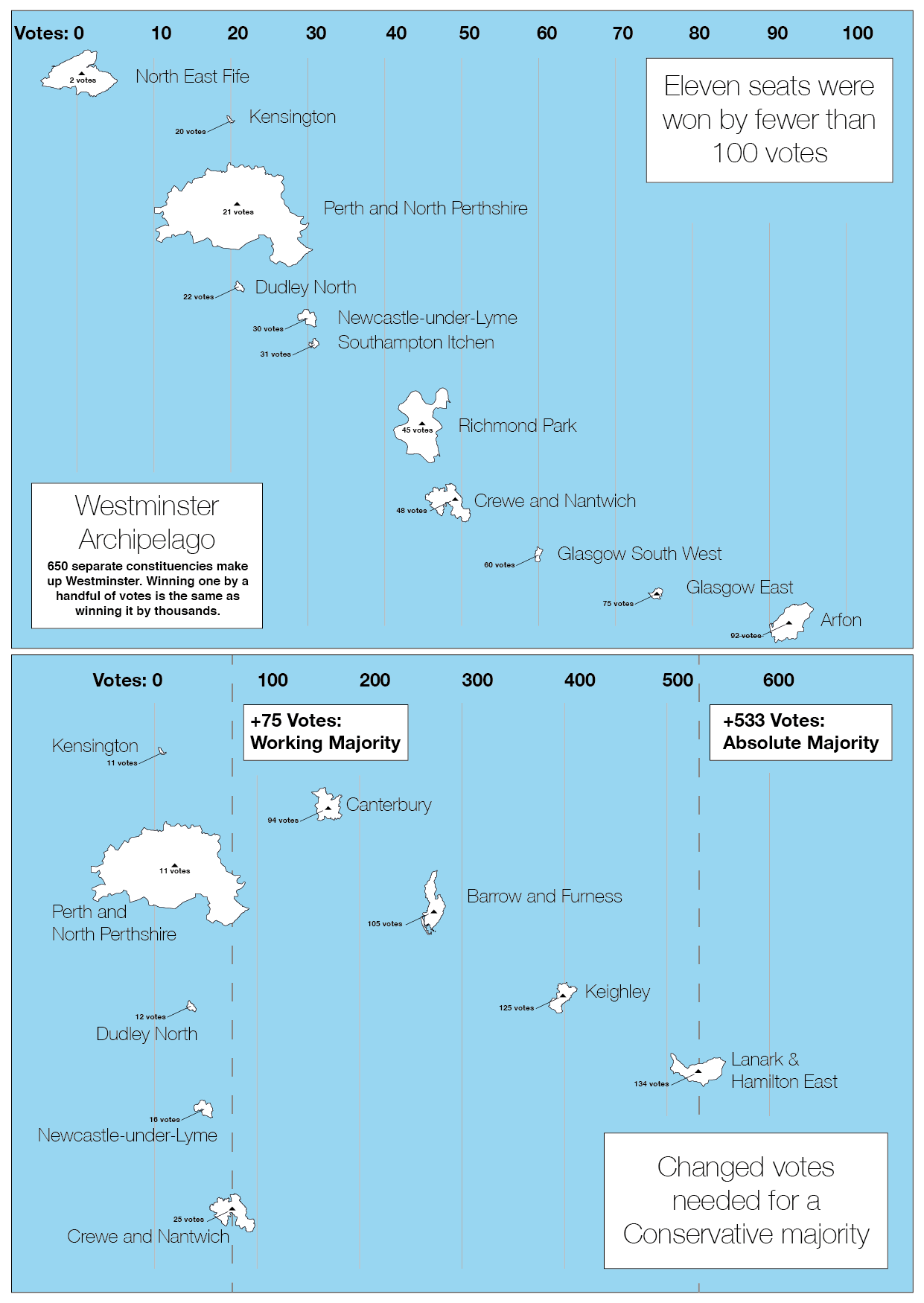

Whilst some seats have been safe for a century, others are highly marginal. The 2017 general election saw an increase in very marginal seats. Eleven seats were won by less than 100 votes. North East Fife was held by the SNP by just two votes. Such are the vagaries of the system that the Conservatives could have won an absolute majority on the basis of just 533 extra votes in the nine most marginal constituencies. A working majority could have been achieved on just 75 additional votes in the right places. Two very different outcomes based on less than 0.0017% of voters choosing differently in 2017.

By placing electoral outcomes in the hands of a small number of voters in a few select places, the electoral system not only gives some votes far more power than others, but is also creating an ever more unpredictable electoral environment. With a changing electorate and increasingly multi-party system, First Past the Post (an electoral system designed to produce single-party majorities in a two-party system) is failing.

Ultra-marginal seats at the 2017 general election (top) and how many votes were needed in key constituencies to form a working or absolute majority (bottom).

A small change in a few constituencies would have significantly changed the outcome of the election.

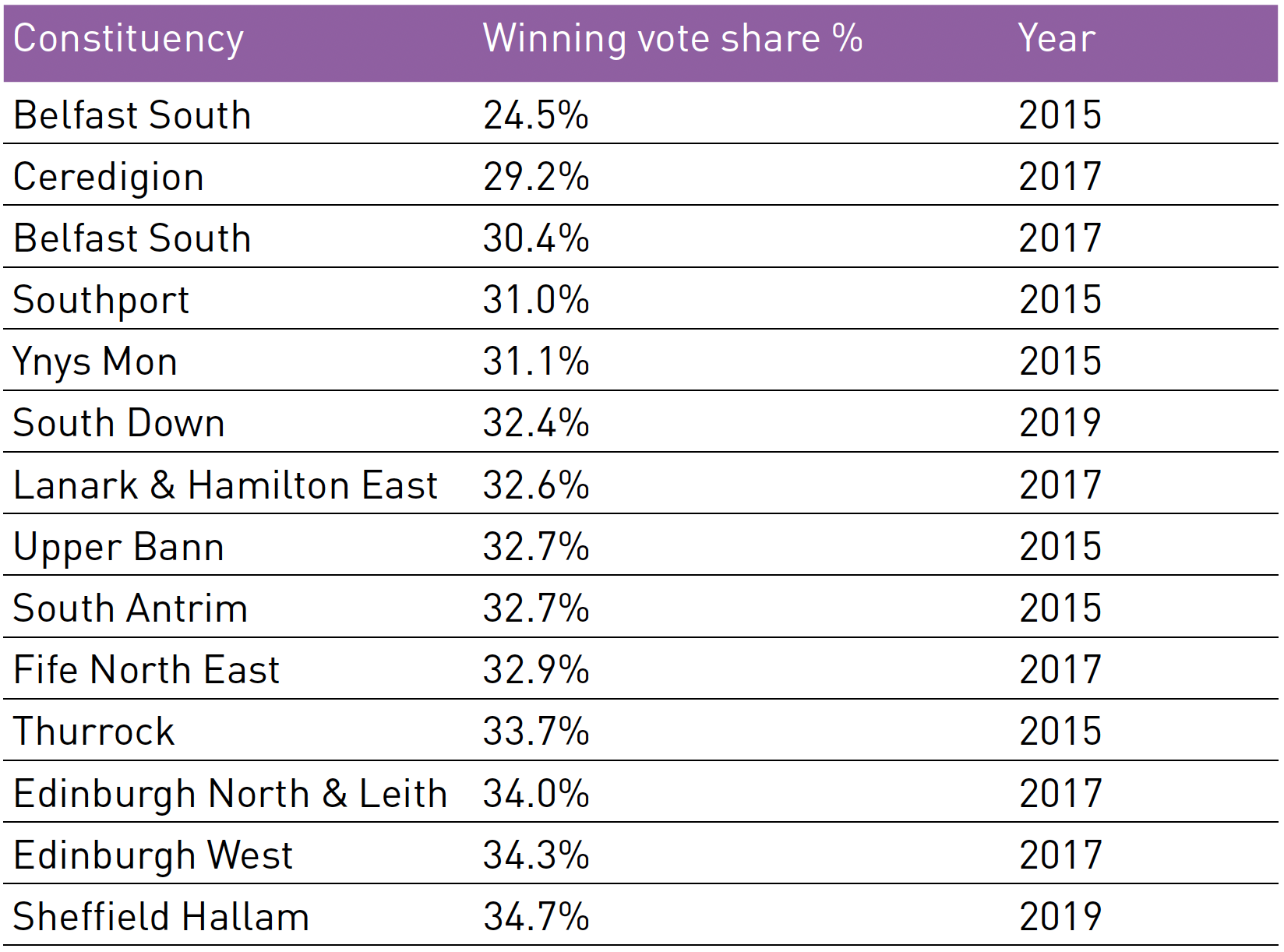

Smallest share of the vote needed to win

In seats where more than two parties are in contention, winners are frequently elected on a small percentage of the vote. The smallest of these in the last three elections was Belfast South at 24.5 percent of the vote in 2015.

Overall, in 2019, 229 of the 650 MPs were elected on less than 50 percent of the constituency vote – in other words, 35 percent of all MPs lacked majority support.

Smallest vote share for elected candidates 2015-2019:

Using FPTP in multi-party contests means the winning candidate is often far short of majority support.

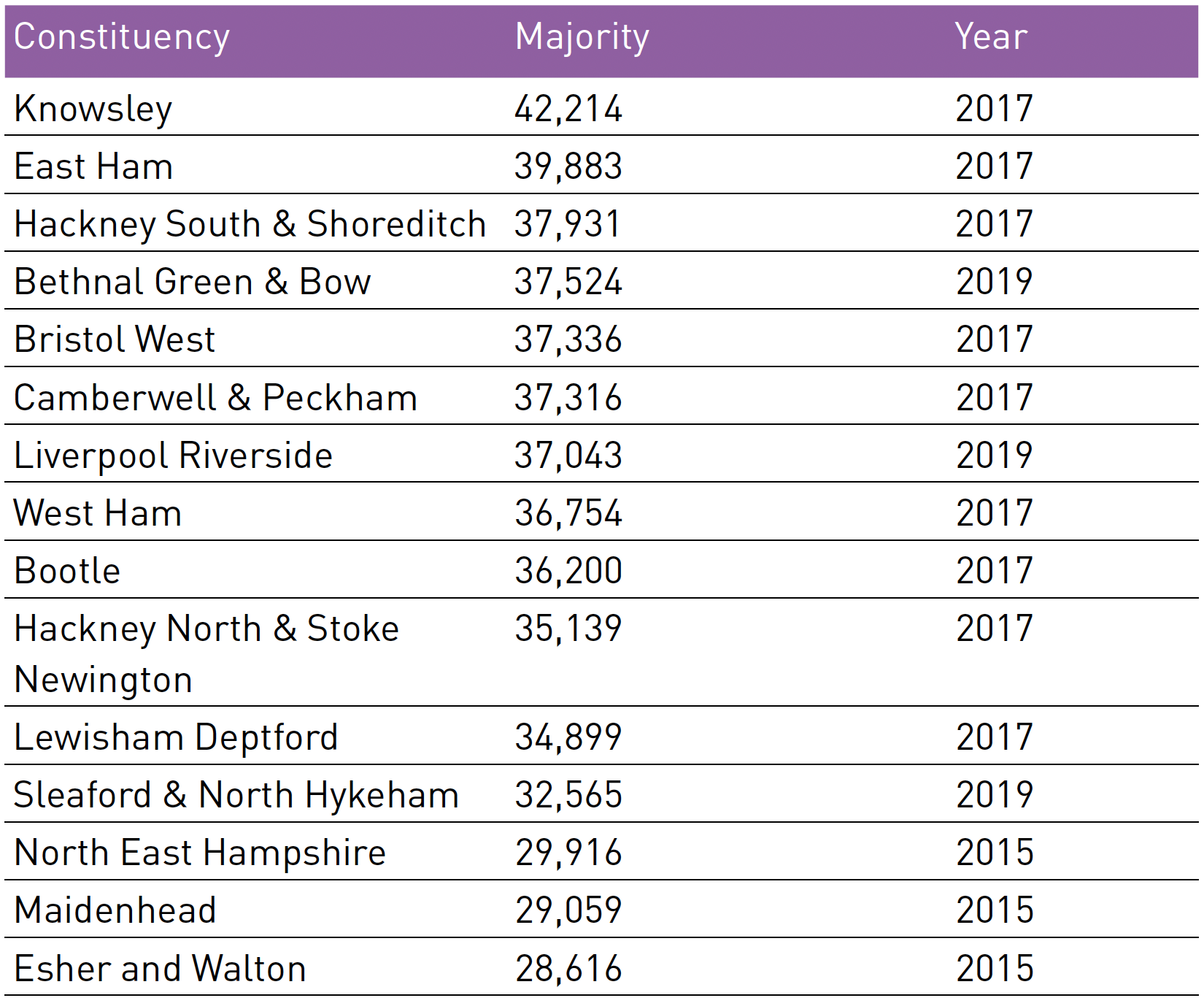

Largest winning majorities

Another symptom of Westminster’s electoral system are candidates winning with huge majorities – piling up votes far beyond the amount needed to claim victory. Though indicative of a party’s support in specific areas, such large winning majorities mean that thousands of votes have no effect on the overall outcome.

The huge majorities won in these constituencies reflect a broader trend of certain votes consolidating in certain areas. The problem of this geographical concentration of votes for parties is that this increased support does not result in greater representation, only larger majorities for those MPs who have already crossed the line. FPTP rewards the most geographically efficient vote spread – which means it wastes a lot of votes which are geographically concentrated.

Largest majorities for elected candidates 2015-2019:

Under FPTP votes often stack up in safe seats creating bigger majorities for those MPs already over the line, but not more seats.

Keep your eyes peeled next week for the next part of the report.

You can visit our website to read the full report.